On Sunday, September 17, at 3pm, prolific author and journalist Beth Winegarner will be discussing her new book, San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History, just published by The History Press, at Bird & Beckett Bookstore. She’ll be in conversation with Courtney Minick, chronicler on her website of all things macabre in California, Here Lies a Story.

Winegarner, 50, was born in Northern California and raised in Forestville in rural Sonoma County. She has lived in Glen Park for twenty years and shares a home with her partner and 14-year-old daughter.

Her book describes, among other topics, the history of the transfer of 150,00 of the city’s graves from its twenty-plus cemeteries to the nearby unincorporated city of Colma from the late 1880s to mid-1900s to make room for the area’s steadily increasing population. Interrupted by World War II, graves were still being moved until 1948. As recently as 2011, remains were moved from an excavation site at the University of San Francisco.

Despite the theme, Winegarner’s writing is lively. It is emotional. It is passionate. And it’s meticulously researched. There’s considerable information online in bits and pieces, but her book lays out the history in one engrossing story. In her extensive citations, Winegarner wanted to create the opportunity for future researchers to not have to reinvent the same information.

“I am the granddaughter of two funeral directors–you could say that death is in my blood,” she writes. Questioned further, she says her family history is more like a coincidence than anything else. She’s been interested in being in cemeteries, and the processes of grieving and remembering the dead have sparked her imagination since she was a teen.

“There’s a story in every headstone,” she says. “It feels like getting to almost meet the people that were here before us. And the statues are really beautiful and there’s a whole language of the symbols that are on gravestones as well, whether it’s a wreath or a sheep or an urn with a veil.”

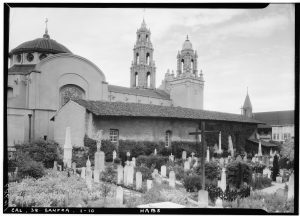

Winegarner felt a distinct emptiness when she moved to San Francisco, the city famous for having no cemeteries. Actually, there are a few remaining cemeteries–Mission Dolores was the first one and later the cemeteries in the Presidio. Mission Dolores is the final resting place of between ten and eleven thousand people. The last burial there was in 1953.

Before the Spanish began settling San Francisco in the late 18th century, the City was home to about 1,500 Ramaytush Ohlone.

Winegarner writes, “An estimated 5,500 indigenous people of the San Francisco Bay Area were buried in and around the Mission Dolores Cemetery, but if you visited the place now, you’d hardly know it.” She purposefully does not include accounts of those villages’ burial sites which have been discovered over time as areas have been redeveloped. “Even though some of that information is publicly available, I don’t have the cultural background to do their stories justice,” she says. “We don’t really belong here,” she adds. “Or if we do, we need to radically alter what we think of as our property.”

In contrast to accounts of the lives of people which invariably begin with the year of their birth, San Francisco’s Forgotten Cemeteries: A Buried History often begins accounts of early settlers with the year of their death. It’s very striking how young people were when they died.

Winegarner explains that most people coming to San Francisco were young, able-bodied men who came to seek their fortune, particularly in the Gold Rush beginning in 1849. In those days disease, serial epidemics, fires, accidents and violence cut lives short on a regular basis.

Interred in the North Beach Cemetery were 800 to 900 of the city’s Gold Rush dead. “This was no tidy, modern cemetery…the caretakers, if there were any, struggled to keep up with the numbers of dead who needed burial,” writes Winegarner.

The diversity of San Francisco from its early times as a city is reflected in its cemeteries. Also reflected is the exclusion of groups due to racism and bigotry. And ignorance, as it was generally believed that to live near a cemetery was to be exposed to disease transmitted by the dead. There were also fears of contamination of the underground water supply.

Winegarner believes this is part of the nature of the San Francisco Bay Area. “As a community journalist for 25 years, the NIMBYism started early and hasn’t gone away. People just want to decide what gets put next to them and what doesn’t, whether it’s mixed-use housing or a hospital or a drug recovery treatment site.”

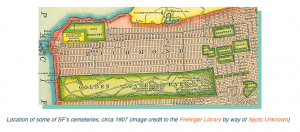

Cemeteries were concentrated in the northeastern part of the city. Each was distinguished by ethnicity, race, fraternal organization (Oddfellows, Masons) or the military (Sailors Burying Ground, US Marine Hospital Cemetery, for example). Mission Dolores was for Catholic burials only. This led to the establishment of separate cemeteries for Protestants, Chinese, Greeks, Russians and Jews. What is now Dolores Park was once the site of two Jewish cemeteries.

The San Francisco National Cemetery opened in 1884, part of a federal network of cemeteries that began with burying the massive number of Civil War dead and later came to include veterans of subsequent wars. Hundreds of anonymous military dead are also buried there.

San Francisco ultimately established a public cemetery, the Yerba Buena Cemetery, later relocated to the sandy wilds of the far northwest and named the City Cemetery, where the indigent were reburied and where golfers now recreate at the Lincoln Park Golf Course and art lovers enjoy the Legion of Honor Museum.

As time went on, six cemeteries, the “Big Six,” were developed as destinations for enjoying nature, picnicking and strolling, dubbed “Garden” or “Rural Cemeteries.” Soon, however, they became neglected and shabby and then people wanted them gone.

There are unusual cemeteries as well. On the Main Post of the Presidio were the burial grounds of the soldiers. But there was also a resting place for the stationed US Army’s beloved pets in a cemetery all their own. Perhaps ironically, these graves are in good condition and were not moved or built over and are open to visitors.

There have been some thirty cemeteries and burial grounds in San Francisco between 1770 and the early 1900s. Other “impromptu” burial grounds have been discovered over time.

Winegarner weaves the history of the various cemeteries with the growth of San Francisco. She writes about how time and again cemeteries were established, in what were the outer lands, for “eternity,” yet progress and an unanticipated growing population overruled a final resting place. Of the Lone Mountain cemetery, the city leaders declared, “…there is room in the Cemetery to bury all of the dead of San Francisco for half a century to come.” These early cemeteries, with the exception of Mission Dolores, lasted twenty or thirty years at most. Urban expansion was relentless. From 1849 to 1852 the population grew from 1,000 to 36,000.

Graves were sometimes relocated multiple times and it was often a very haphazard undertaking. Many San Franciscans who’ve been here for generations are unable to locate where their loved ones are buried in unmarked graves. Few records were kept.

Other world cities have moved their dead to outlying areas too, because of burgeoning populations, notably London and New York.

People had a prurient curiosity about watching the graves being dug up. “The spectacle of digging up remains to make room for the Main Library drew people from all over the city, who wanted a glimpse of what lies beyond the grave,” writes Winegarner.

The material of gravestones was often “recycled,” as we would call it today. The concrete was used in a multitude of ways to keep building the growing city.

Graves were also left behind, an estimated 50,000 to 60,000, under the city streets we walk and the buildings and shops in which we conduct our daily business, proud landmarks and mundane structures alike: a parking garage, the Asian Art Museum, Target and Forever 21 stores, KPIX and KCBS studios, the Infinity condominiums, Salesforce Tower, and lovely Victorian and Queen Anne homes, to name a few.

The consequences to the living are disconnection from their ancestors and their history, notes Winegarner. “Graveyards represent spaces for grief…that have been denied to many in our modern lives.”

Is it possible that any human remains have been uncovered in Glen Park? Winegarner doubts it, but “It would not surprise me at this point,” she says. Burials were banned in the city in 1901 and most of Glen Park was not developed until later. Possibly indigenous people who died here were buried here. Certainly there was no formal burial ground. Yet someday someone might discover remains in their backyard on a renovation project.

There are alternatives to burying the dead. Winegarner says more than half of people opt for cremation today. The San Francisco Columbarium, built in 1899, was the first of its kind on the West Coast and has room for 8,500 cremated remains.

New methods are being developed and gaining interest, such as “eco-friendly” human composting and alkaline hydrolysis. We need to be thinking about this as the cemeteries of Colma and elsewhere inevitably fill up.

Winegarner knows it’s not feasible to right the wrongs of the past, to unearth tens of thousands, try to identify them with DNA, and find space for them in Colma. Yet she thinks more can be done to memorialize them and make people aware of when they are on hallowed ground. Recently Lincoln Park has installed an informational panel where the dead lay below. A plaque at the Marine Hospital Cemetery reminds passersby of the sailors under the dunes. (The story of this transformation is one of the more shameful episodes described in the book.)

Winegarner has lots of ideas to memorialize the dead lying beneath our feet.

As she writes in her book, “We should include these places on maps, erect durable signs and monuments and cease pretending like they are no longer there. We have done this in a few places, but we need to apply this practice in many more…In today’s world, many people will tell you that the remains of the dead are not significant, no more than fertilizer for the soil, and yet disrespect for the dead feels deeply wrong…No matter how we might feel about what happens to our bodies when we die or about how our loved ones’ remains are handled, we owe it to these early San Franciscans—and ourselves—to respect them.”